My dad used to water the weeds.

The backyard of my childhood home in Live Oak was “typical white trash” an ex-girlfriend once said. She was a bitch, but she was right about that. Often the weeds would grow so high they would completely obscure the three broken down cars that sat back there. “Finding” a car in your yard is the very definition of redneck, says Jeff Foxworthy.

I was maybe 10 years old when my brother braved the thicket to retrieve one of our meticulously crafted, duct tape-wrapped socks masquerading as a baseball, and emerged saying incredulously, “Dad is watering the weeds!” We followed the running hose from the side of the house, meandering through and disappearing into the jungle. We both laughed and thought, Why in the world would he do such a thing? Then promptly forgot about it.

But it became one of those seemingly random childhood memories that resurfaced often in the angst-ridden mind of my young-parent 30s. I struggle with the meaning and value of these memories. Are they profound parenthood lessons, crystallizing now that I have some capacity to appreciate their meaning and interpret them? Or just shit that I remember?

Addison loves hearing these anecdotes of my childhood. “Daddy Stories” we call them. Stories about me and my friends playing our made-up games, running around the neighborhood free of non-existent helicopter parents; my family piling into a Station Wagon at midnight for a summer trip to Oregon; the strange kid, Matt Gokey, who would piss in the corner of his room. Addy hangs on to every word of these stories, peppering me with insightful questions.

The night I told her the Daddy Story of when grandpa watered the weeds, she asked the obvious question, “Why did grandpa water the weeds?” Well, fuck, I thought. I never asked him! I offered that maybe he just saw things differently. Maybe he sees beauty where others do not? It sounded like the premise of a great children’s book; a lesson on appreciating unseen beauty and hidden qualities. I liked this explanation I gave her.

While I didn’t know the answer as to why he watered the weeds, I knew it was not that. And I knew if I ever asked him, the answer, whatever he gave, would be decidedly less profound.

I kissed Addy goodnight, climbed down from her loft bed and went downstairs to my wife and went down a path that led to the disintegration of my family. I was already well down this path, but now it was real. Now there was hurt. Emotions bearing the most awful blunt force collided with our little lives so painfully, that my wife later wanted nothing to do with the simple kitchen table on which we sat that night, lest it ever conjure up the crushing heartache of that terrible conversation. I left. And the table now collects dust in my best friend’s garage.

I sit now, what seems like a fucking lifetime later, surrounded by scattered remnants of that life: a globe my wife gave me the day I graduated with my journalism degree (“Something a journalist would have on their desk,” she had said); my closet full of clothes seen in hundreds of pictures spanning the lifetimes of our kids; and their toys. Fuck, their toys.

Every time I look at their neatly put away toys, I remember my first New Jersey winter. Alone, and awaiting my wife and infant daughter’s arrival in three months, I unpacked our household goods in our newly rented townhome 3,000 miles away. I set Addison’s toys out around the house, as if she was in the other room waiting to come out and play with them. A lonely, cold house full of untouched children’s toys will lead one to question more than just a tough career choice.

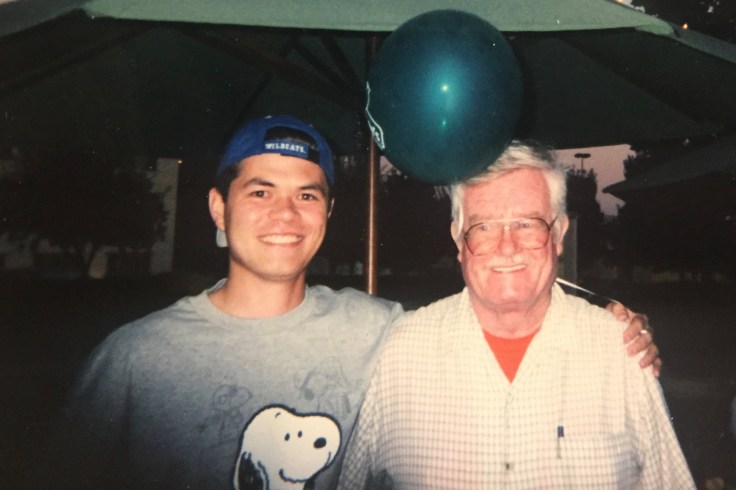

I have a room now in my dad’s house. He is in the twilight of his life, inching toward oblivion after a debilitating stroke left him fleetingly forgetting his own children’s names. Living with him again, if even for such a short period of time while we find him living assistance, is so ironically fitting. Just like during my childhood, he shuffles past my room every night, pausing at my door to say goodnight, only now it is the other who battles depression and is consistently drunk.

I talk to him every day now, more than I have in 20 years. Despite every opportunity, I don’t ask him and I never will. I don’t ask him because I want MY answer, not his.

The Toyota Celica was the car we took to our first family Disneyland trip. We had just arrived from the Philippines, as the story goes, we made the trip while my mom was pregnant with me and she held my infant older sister in her lap the entire drive down. The red Station Wagon was the car in which we laid blankets in the back and rode (again, without seat belts!) all the way to Portland to see our grandmother every summer. It was also the sight to elicit a hallelujah while baking in the summer afternoon, waiting for a ride home after a long day at the public swimming pool. The Plymouth Reliant is a total misnomer. The piece of shit must have broken down before I formed a single memory of its running existence.

Grandpa could not let them go. He used to be a mechanic who loved to work on cars. He used to be a husband before his wife left him. He seemed to cling to these memories for his very life. But I think he also could not bear to see them. So he fostered the growth of ugliness to obscure them; to mask the pain, but hold the memories close to heart.

He wanted the pain there and not there. He welcomed his suffering, drip by drip, come wisdom or not.

That’s why he watered the weeds.

And I see now, that I am indeed, my father’s son.

Very interesting take, I had no idea you had a journalism degree and your Filipino? Wow who knew.

LikeLike

I’m sure I cooked you some lumpia before. Lol

LikeLike

Beautifully written, Mr Brightside. I can understand that pain and also wanting your own answers and understanding to questions perhaps everyone needs to find for themselves…if they choose to. It’s just going down that path of trying to find understanding can be so painful in and of itself. And then if we gain some insight, what then do we do with it? Because now it’s ours.

LikeLike