And over this rainbow

I heard a shot

Fire up from a ghetto

I didn’t think you’d follow

Just didn’t know

The sky was this shallow

“The way down is harder.”

The remark gave me pause because my brother, Bobby, is rarely serious. People unacquainted with his quirkiness could easily mistake it for clinical insanity. It was late July 2016, and we were halfway up Mt. Shasta and I had been listening to his “Fuck it all, let’s disappear ‘Into the Wild’ like Christopher McCandless” nonsense for almost a day now.

He wasn’t the only one feeling reckless. It was only six weeks earlier on Father’s Day morning a disc in my lower back blew out (again) causing me to collapse onto the floor of my apartment. Through clenched teeth, I beckoned my 8-year-old daughter to get me my phone so I could dial 9-1-1 as my 4-year-old son looked on. The firemen carried me out the door on a spine board to a waiting ambulance and I spent most of the afternoon lying on a gurney in an emergency room’s crowded hallway.

Bobby, a highly experienced hiker, offered to postpone our long-planned climb. I adamantly told him that I would climb Mt. Shasta myself if he didn’t fly his ass over from Hawaii. He caved, and here we were, resting overnight at Lake Helen at about 10,400 feet, when Cassandra here uttered his prescient warning of impending doom on our decent. “That’s when most accidents happen.”

Mt. Shasta is a 14,179-foot active volcano that sits at the southern tip of the Cascade Range and dominates the Northern California landscape. While not exactly K2, it is a respectable exploit for a novice mountaineer. “It’s no joke,” my friend, Mike from Mount Shasta, warned me. “People die up there,” my friend Marcos texted me after he opted out at the last minute. Melodramatic perhaps, but true.

Earlier that July, an experienced climber died after slipping and striking a boulder after an uncontrolled slide. And another climber would die similarly a few weeks later in August. During our first rest at Horse Camp, a ranger reminded us to remove our crampons before glissading (sliding on your butt while dragging your ice axe as a break during the decent), so we don’t catch a hidden boulder beneath the snow and break both our legs like a guy did the day before. He required a helicopter medevac off the mountain.

I had never climbed a mountain so perhaps those stories should have concerned me, but they didn’t. I just wanted to do it because I wasn’t on top of my shit mentally.

To hell with my disc. I thought I would sooner collapse from the weight of my overburdened conscience: punishing guilt due to my recent separation; searing self-doubts I now had as a father; utter floundering in my career; creeping and ineluctable financial insecurity; an estranged paramour. Already buried under my own avalanche of millstones, my back troubles were poetic.

In perhaps a subconscious effort to be someone else, I had grown out my ridiculous, half-Asian excuse for a beard just for this climb. I hated facial hair, but I hated looking in the mirror even more.

I’m not sure I slept that night at Lake Helen. I neglected to bring a sleeping pad and my cheap sleeping bag was better rated for camping in a suburban backyard under a Dora the Explorer tent. The sunflower seeds and Army MRE (Meal Ready-to-Eat) ration I ate hardly left me sated.

At about 4:30 a.m. we continued our ascent up Avalanche Gulch, Mt. Shasta’s most common climbing route. I wheezed in the increasingly thin air and too often had to stop and catch my breath. But in those moments, I turned around to admire the most sweeping, soul-nurturing views of my Northern California home I had ever seen.

We next encountered Red Banks, a long rock formation that, from the bottom of Avalanche Gulch, looked like a wall that you’re supposed to assault. “Just pick a chute,” the ranger at Lake Helen told me. The chutes being steep, narrow passages through the rock formation that open out like gates into the top of the expansive gulch. With angles of up to 35 degrees, it can be the trickiest and most dangerous part of the route.

After Red Banks, we climbed the aptly named Misery Hill, where for our late-season climb the snow gave way to volcanic scree and back to snow again when we reached the top. Once over Misery Hill, Mt. Shasta’s summit finally became visible across a snow-covered plateau.

I reached the summit late in the afternoon. I don’t remember what I wrote in the registry posted there, but I’m sure it was something profound and fitting for one of those workplace motivational posters I always make fun of. I had planned to let loose a primal, guttural scream in some kind of hope to exorcise my troubles, but I couldn’t muster the strength, so I settled for a picture of me meekly flexing my biceps.

We began our descent in the afternoon. The day before, when the clerk at Shasta Base Camp handed me my rented ice axe, I noticed it didn’t have a rope on the handle to secure it to my wrist like the others did. I didn’t say anything, obviously, because that’s what a responsible and forward-thinking person would have done. I saw it more as a prop to feel like a real mountaineer rather than a tool to self-arrest a fall.

On the descent, I found it easy to get distracted by the incredible vista. The precariousness of the steep slopes and the ramifications of a misstep were front and center, rather than behind you as they were on the way up when the boring ground completely encompassed your view.

It was getting late, so we chose a closer and steeper chute at Red Banks. One that looked well traversed and was glistening with melting snow. I was slowly sidestepping through the chute, when I lost my footing and slid a few feet before falling onto my back. I lost my trekking pole and ice axe almost immediately as I slid down through the chute flailing for something to grab and spinning like a Vitruvian Man fidget spinner.

I quickly reached the bottom of the chute where my right leg caught a crevasse that had formed against the rock wall and jetted slightly out into the chute, arresting my slide and whipping my torso forward, slamming my face into the snow. Had I hit that crevasse in any other way I would have likely broken my hip or much worse.

The crevasse was deep enough to fall in to, so I instinctively pulled my leg out. Only I neglected to secure myself first, so I promptly continued my tumble out of the chute and into the open, boulder-peppered Avalanche Gulch, accelerating quickly. Now I could manage the scream, but now it was muffled by the snow raking my face and sounded more like a smothered whimper.

I flipped over and spun around frantically as I tried to stop myself. Eventually, I stabilized and found myself on my stomach, sliding feet first punching into the snow with my fist hoping I could stop myself before a boulder did. With my entire right forearm boring into the snow, I gradually slowed down and mercifully came to rest near The Heart.

In the few hundred feet I had slid, I cannot remember what exactly crossed my mind, but had I not consumed that constipation-inducing Army MRE, I most certainly would have shit my pants.

In incredible pain and unable to move it, I was pretty sure that my left arm was broken, but I saw no protruding bones. My ankle was sprained and I felt an ominous, familiar tweak in my lower back. I laid there panting, not daring to move lest I dislodge myself. I dug the heels of my crampons into the ground and just waited.

When Bobby reached me about 30 minutes later, I told him I didn’t want to move. He called 9-1-1, but apparently, we were too high for a rescue helicopter to reach us. Bobby handed me the phone and the ranger, after acknowledging my broken arm, asked me if I could stand up. I said I could. Then he insisted that if I could stand, then I could walk. And if I could walk, then I could make my way down to Lake Helen where the helicopter could land, or rangers could ascend from the trailhead and carry me down if I needed it. It would take far too long for the rangers to ascend on foot to my location.

The ranger was sympathetic and encouraging, but I sensed something else in his tone. It was likely just my preference for drill sergeant incitement, but I thought this guy must have seen much worse and was just telling me to walk my ass down the mountain.

Bobby told the ranger that we would call them again when we reached Lake Helen. When I stood up, I looked down at Lake Helen and thought I’d die before I could reach there. Sidestepping down through the snow, pain shot from my shoulder on the impact of each step.

Bobby had recovered my ice axe, and although the very last thing I wanted to do at that moment was slide down a mountain again, I decided to try glissading. Although I hadn’t bothered to learn how with two hands, much less one.

I was able to control my slide despite my broken arm, but I imagined it was like surfing right after a shark had just bitten your leg off or floating down a lazy river in an inner tube right after a crocodile had eaten your arm; shit that would have been a blast but for one particular set of circumstances.

We finally reached Lake Helen just before sunset. A couple of hikers immediately approached us and said they heard someone was injured and offered to help. A young man, who I will affectionately describe as a hippy, introduced himself as Ian and suggested my shoulder might be dislocated. He offered to try setting it, but his caveat of, “if it’s actually broken, I might make it worse” dissuaded me from allowing him to try whatever Mel Gibson trick he may have had in mind.

Below the snow covered Lake Helen, most of the remaining descent to the trailhead was through rocky scree and wooded areas. The ground we would cover was almost four thousand feet in de-elevation and was roughly four miles. While I didn’t look forward to descending the mountain in the dark, staying another night and trying to sleep with my broken arm was even more unappealing.

I was now confident I could make it to my truck at the trailhead. We called the rangers and advised we would make it to the hospital on our own.

Ian and his friends were hiking the Pacific Crest Trail and were in no particular hurry, so despite losing a day, he and a friend offered to help carry some of my gear back to the trailhead with us. Leaving some of our gear behind, we continued our descent just before nightfall.

Exhausted, hungry and becoming severely dehydrated, cramping became an issue by the time we reached Horse Camp again. I was cramping not just in my legs, but in my right arm that had been supporting my weak arm by propping it up with a trekking pole.

We finally reached the truck and drove to the town hospital. A little after midnight, I walked into the emergency room and wanted to fall to my knees and scream, “HEEEEELP MEEE,” but I played it cool and nonchalantly said, “I think I broke my arm,” handing over my license and insurance card.

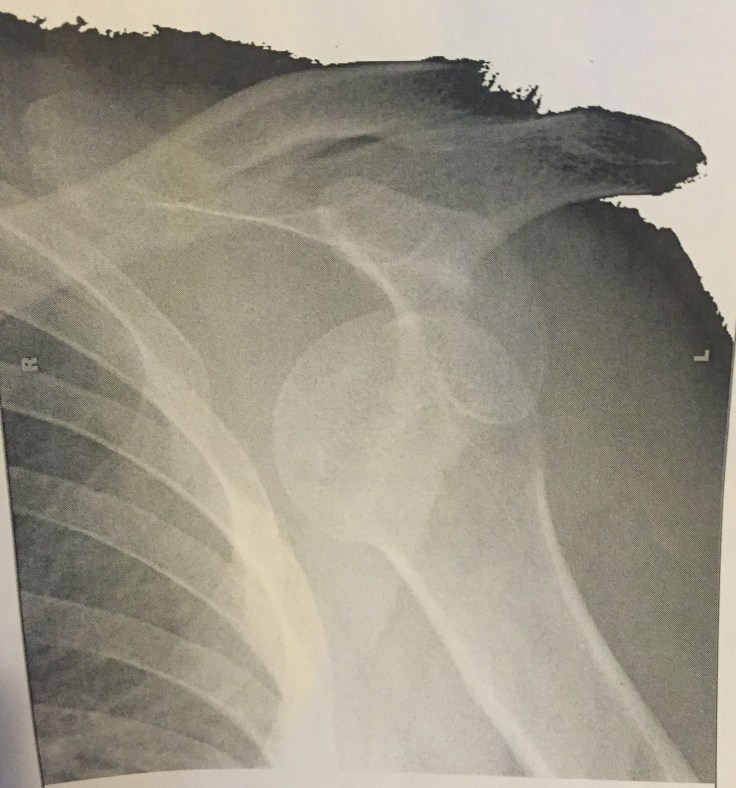

“Is it out?” I later asked the x-ray technician as he looked at my film. “It’s way out,” he responded, disconcerting me with the way his eyes got big with his slightly elongated “waay.” After the medications kicked in I fell asleep, but awoke briefly as a doctor reduced my shoulder.

We left the hospital after 3:00 a.m. and got a hotel room for Ian and his friend. In the morning we treated them to breakfast before dropping them back off at the trailhead. To this day, I still marvel at their kindness and selflessness; a courtesy I’m not sure I would have extended to a stranger under similar circumstances. Without Ian and his friend’s help, and especially their water, Bobby and I just might have gone the way of Christopher McCandless.

After my herniated disc six weeks earlier, I was placed on a modified duty at work. Now I found myself back in the nurse’s office with my arm in a sling, further modifying my modified duty. A supervisor promptly pulled me into a copy room in front of my co-workers and berated me for being “irresponsible.”

“What were you thinking?” she asked me. I don’t remember my answer. I only remember the question because of the ridiculousness of its self-evident answer and the resentment I felt at the naked affectation behind its asking. Why would a person whose life was imploding want to go climb a mountain? These are not Socratic questions.

Another supervisor admonished me over the appearance of my beard. “I’m not a beard guy,” he said, offering the kindest example of the universal ridicule I received. Then he likened the “unprofessional” display of my beard to walking around the office with a t-shirt that said, “Fuck You.” The beard was patchy, but damn.

When the sling came off I got my first tattoo. Long my favorite poem, “Invictus” spoke to me of a different kind of perseverance. A vehemence that saw me through previous bouts of self-doubt. I embraced the irony of declaring myself “invincible” when I had two current outstanding ER bills for two different visits within two months. I wanted to rage at what I was going through. I taunted it and dared it to hurt me more.

Then I shaved that stupid fucking beard.

It’s been almost three years since I fell off a mountain. While the occasional pop in my shoulder takes me back up there, I can now look at the beautiful pictures Bobby took of our climb, one of which I turned into a poster, without wincing at the memory of so much pain. Bloody, but unbowed.

“Absolve you to yourself and you shall have the suffrage of the world,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson, in his treatise, “Self-Reliance.” Know who you are and be true to yourself, and you’ll be unconquerable. And Arthur C. Clarke once said, “The best measure of a man’s honesty is not his income tax return. It’s the zero adjust on his bathroom scale.”

I’ve since dwelt on self-honesty and acceptance with the focus and discipline of a monk. And like a Shi’ite during Ashura, I have flagellated myself with the sharpest and most cutting truths that have bled the brightest blood over my wide-open eyes. It was the only way out of that abyss of self-hatred and guilt in which I had foundered.

I guess Bobby really was a prophet: the descent is the climb. Majestic views are on postcards that can be bought for 50 cents. Pulverizing self-realizations may break you. They may even shatter your mind. But they are priceless; purchased with blood and tears. They are your markers on a path to your true heart. They are the journey’s reward, and they are only earned on the way down.

I’ve learned that it’s forgivable, even necessary, to wallow in guilt and self-pity for making your most heart-rending decisions. To rip yourself to shreds for your most awful mistakes. But there comes a point when you’ve got to call a truce. When you’ve drawn enough blood that you’re going to die up there.

Or you can accept who and where you are… and come down to heal. And maybe if you’re lucky enough, strangers and friends, old and new, will be there to help you along.

When I fell out of the walled chute and into the open Avalanche Gulch there was no point of reference; only white and blue. A free fall into the unknown is terrifying. The only thing worse could be the realization that there is nothing to arrest your fall even if you could see it and grab it; that you’re at the mercy of an external force and only it will decide how this will end, gradually or with blunt force.

It has been hard. It has been painful beyond words that I can conjure to describe.

Being on top was sublime, but it was the fall that I had come for. Only now, when I stare at Bobby’s picture of me and the looming summit, have I come to realize that it was in that moment, when my foundations slipped away and I saw nothing to embrace save my own elusive truths, that Mt. Shasta has given me what I have desperately sought; peace with myself.

Leave a comment